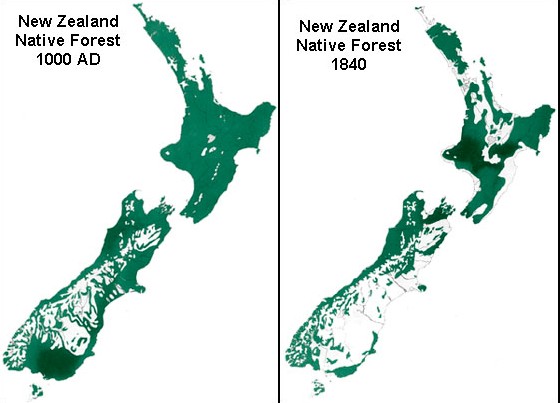

Much of the material on this site focuses on the impacts of European settlers on the New Zealand environment. But of course the environment was neither untouched nor pristine when organised European settlement began in the 19th century. As can be seen in the forest cover diagrams in the earlier post, Destruction of our forests over time, the Maori also had a significant impact on New Zealand’s forests, albeit over a much longer period of time (centuries as opposed to years). Between the beginning of Polynesian settlement in New Zealand around the fourteenth century and the beginning of organised European colonisation in the nineteenth century, it is estimated that forest cover was reduced by about half, largely through fire. Continue reading

Much of the material on this site focuses on the impacts of European settlers on the New Zealand environment. But of course the environment was neither untouched nor pristine when organised European settlement began in the 19th century. As can be seen in the forest cover diagrams in the earlier post, Destruction of our forests over time, the Maori also had a significant impact on New Zealand’s forests, albeit over a much longer period of time (centuries as opposed to years). Between the beginning of Polynesian settlement in New Zealand around the fourteenth century and the beginning of organised European colonisation in the nineteenth century, it is estimated that forest cover was reduced by about half, largely through fire. Continue reading

Author: envirohistory NZ

The ultimate paradox?

Children at Toko Primary School, Taranaki, planting trees on Arbor Day 1900. In the fields around them, the devastating effects of the milling and burning of forest that was occurring throughout the country can clearly be seen. [Photo not to be reproduced without the permission of Alexander Turnbull Library, ref 1/2-003378-F. Acknowledgments to David Young for sharing this poignant photo in Our Islands Our Selves.]

Peacock Springs – creating birds from stones

The history of Peacock Springs Wildlife Park is a story of how, through twists of fate and the convictions and actions of inspired individuals, an environment can be transformed beyond anyone’s expectations – both as a visual landscape and in terms of its functions and purpose. It also challenges us on our assumptions about the polarity of the relationship between the “exploitation” and “conservation” of nature.

The history of Peacock Springs Wildlife Park is a story of how, through twists of fate and the convictions and actions of inspired individuals, an environment can be transformed beyond anyone’s expectations – both as a visual landscape and in terms of its functions and purpose. It also challenges us on our assumptions about the polarity of the relationship between the “exploitation” and “conservation” of nature.

In the 1950s, Lady Diana Isaac and her late husband Sir Neil Isaac, founders of Christchurch company Isaac Construction Ltd, bought a house in Harewood, on the outskirts of Christchurch. Having grown up in the English countryside, Lady Isaac wanted to have a house with some land out in the country. However, after digging a lake to irrigate their garden they discovered the property had what Lady Isaac later described as “the worst land in Canterbury”, comprising mostly of shingle – perhaps not altogether surprising given its proximity to the Waimakariri River. But the shingle was found to be a very high quality and the Isaacs began commercial quarrying on the site in 1965, which continues today. Continue reading

What is natural? The case of the Christchurch Port Hills

When the author lived in Christchurch, she found that many Cantabrians would become highly impassioned with even the suggestion of a development threatening the tussocked landscape of the Port Hills. The author even struck cases where people opposed native tree-planting projects because they would detract from the “natural tussocked landscape”. Certainly, it is hard to find a Cantabrian who is not fond of the soft, light golden-tinged tussocked hills that surround Christchurch, nor one who would question the “naturalness” of this landscape.

When the author lived in Christchurch, she found that many Cantabrians would become highly impassioned with even the suggestion of a development threatening the tussocked landscape of the Port Hills. The author even struck cases where people opposed native tree-planting projects because they would detract from the “natural tussocked landscape”. Certainly, it is hard to find a Cantabrian who is not fond of the soft, light golden-tinged tussocked hills that surround Christchurch, nor one who would question the “naturalness” of this landscape.

Yet, the tussocked hillsides of which Cantabrians are so fond are not natural, but a result of human intervention over time – through fire, logging and grazing. Some of this human-caused change occurred prior to European settlement, which is perhaps why the current landscape has become so fully ingrained in the collective psyche as being both natural and beautiful. Continue reading

Were the Scottish really greener?

Did Scottish and Irish settlers bring particular land management practices with them to New Zealand? In particular, did the Scottish have a strong conservation ethic which made them “greener” than their fellow-settlers, as is sometimes claimed? These were some of the questions addressed by Professor Tom Brooking (University of Otago) at a conference in Aberdeen which explored the environmental histories of Scottish and Irish migrants to countries of the “New World” such as New Zealand, Australia and Canada.

Did Scottish and Irish settlers bring particular land management practices with them to New Zealand? In particular, did the Scottish have a strong conservation ethic which made them “greener” than their fellow-settlers, as is sometimes claimed? These were some of the questions addressed by Professor Tom Brooking (University of Otago) at a conference in Aberdeen which explored the environmental histories of Scottish and Irish migrants to countries of the “New World” such as New Zealand, Australia and Canada.

At the conference, United Kingdom based Environmental Historian Dr Jan Oosthoek interviewed Prof. Brooking and asked him about the environmental practices of Irish and Scottish settlers in New Zealand. He also asked him to talk about what makes New Zealand’s environmental history unusual and unique.

Photo: Scottish-born politician, explorer and conservationist, Sir Thomas McKenzie (standing, centre) with party in Southland, between 1908-14. McKenzie was instrumental in making Fiordland a national park and was a founding member of the Forest & Bird Society. Used with permission from Alexander Turnbull Library ref PA1-0-307-42.

Click here to download the podcast (scroll down to Podcast 19)

A lesson not learnt – Lake Manapouri

In his history of conservation in New Zealand, Our Islands, Our Selves, David Young provides us with an anecdote that illustrates that the way we understand and value our environment does not always develop following an upwards trajectory through time.

In his history of conservation in New Zealand, Our Islands, Our Selves, David Young provides us with an anecdote that illustrates that the way we understand and value our environment does not always develop following an upwards trajectory through time.

He relates how in 1903, two engineers, L.M. Hancock (from California) and Peter Hay, were commissioned to report on the hydro-electric potential of New Zealand’s lakes and rivers. Their 1904 report drew the following conclusions about Lake Manapouri: “It is not likely, for scenic reasons, that a high dam would be build at Manapouri. The present beauty of the lake is worth preserving to its fullest extent.”

Yet, 60 years later, the government began work on a hydro-electric scheme that would raise the level of the lake 26 metres. It was only after an unprecedented level of public opposition over more than a decade – including a petition of 264,900 signatures – and ultimately leading to the downfall of the National government, that the lake was saved from this fate.

Picture above: “After Rain” (Lake Manapouri), by Tim Wilson. Used with permission from artist.

The opening up of the Manawatu – the “waste land of the Colony”

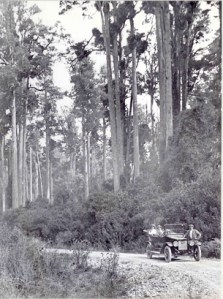

As Lois Hall outlines in her history of the Pohangina Valley, large areas of open grassland such as those found in Canterbury and eastern Hawkes Bay had been quickly settled in the 1840s and 1850s, mainly by more wealthy settlers. But by the latter part of the nineteenth century, the government turned its focus to the provision of land for the settlement of those of lesser means and the descendants of the original settlers who sought to own their own farms. Attention turned to regions that were still forested and undeveloped, such as the Manawatu and western Hawkes Bay. Continue reading

As Lois Hall outlines in her history of the Pohangina Valley, large areas of open grassland such as those found in Canterbury and eastern Hawkes Bay had been quickly settled in the 1840s and 1850s, mainly by more wealthy settlers. But by the latter part of the nineteenth century, the government turned its focus to the provision of land for the settlement of those of lesser means and the descendants of the original settlers who sought to own their own farms. Attention turned to regions that were still forested and undeveloped, such as the Manawatu and western Hawkes Bay. Continue reading

Papaitonga – hidden jewel of Horowhenua

Papaitonga is a dune lake in the Horowhenua coastal plain. It is surrounded by a very rare remnant of coastal north island forest. Just south of Levin, the 135 hectare Papaitonga Scenic Reserve is a little known but ecologically and historically remarkable place [click here to view map].

Papaitonga is a dune lake in the Horowhenua coastal plain. It is surrounded by a very rare remnant of coastal north island forest. Just south of Levin, the 135 hectare Papaitonga Scenic Reserve is a little known but ecologically and historically remarkable place [click here to view map].

The reserve contains the only intact sequence from wetland to mature dry terrace forest in Wellington and Horowhenua. It is an important refuge for birds that depend on wetlands or lowland forests for their survival. Papaitonga is home to waterfowl and wading birds as well as forest species on the lake’s margins. However, like many remnant wetland forests, the health of this wetland forest is threatened by a receding water table. The reserve is surrounded by farmland which draws on large volumes of water for irrigation. Continue reading

From “swamps” to “wetlands”

Through time, not only has our environment been transformed, but also the way we perceive it and the words we use to describe it. No example illustrates this better than the “swamp” to “wetland” transformation. When European settlement of New Zealand began in earnest about 150 years ago, about 670,000 hectares of freshwater wetlands existed. By the 20th century, this had been reduced to 100,000 hectares. Continue reading

Through time, not only has our environment been transformed, but also the way we perceive it and the words we use to describe it. No example illustrates this better than the “swamp” to “wetland” transformation. When European settlement of New Zealand began in earnest about 150 years ago, about 670,000 hectares of freshwater wetlands existed. By the 20th century, this had been reduced to 100,000 hectares. Continue reading

Totara Reserve: from exploitation to conservation

Totara Reserve is situated in the Pohangina Valley on the eastern side of the Pohangina River, in the Manawatu [click here to view location]. It encompasses an area of 348 hectares, much of it podocarp forest, made up of totara, matai, rimu and kahikatea, as well as some black beech.

Totara Reserve is situated in the Pohangina Valley on the eastern side of the Pohangina River, in the Manawatu [click here to view location]. It encompasses an area of 348 hectares, much of it podocarp forest, made up of totara, matai, rimu and kahikatea, as well as some black beech.

Its history as a reserve began in 1886, when it was gazetted under the provisions of the State Forests Act (1885) as a ‘reserve for growth & preservation of timber and for river conservation purposes’. This at a time when the area was been ‘opened up’ for settlement – settlement in the Pohangina Valley area began with Ashhurst in March 1879.

In 1932, a portion of the Reserve was designated as a Scenic Reserve under the provisions of the Scenery Preservation Act 1908, and vested in the Pohangina County Council. Continue reading