In 1870, Colonial Treasurer Julius Vogel introduced a public works and immigration scheme, under which suitable immigrants would be settled along the projected lines of the road and railway. The idea was that the construction work for this infrastructure would support the settlers until they could develop farms on the blocks of land allotted to them.

In 1870, Colonial Treasurer Julius Vogel introduced a public works and immigration scheme, under which suitable immigrants would be settled along the projected lines of the road and railway. The idea was that the construction work for this infrastructure would support the settlers until they could develop farms on the blocks of land allotted to them.

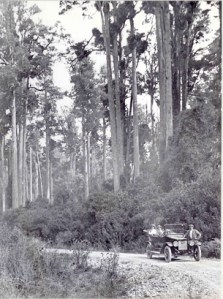

At this time, the Manawatu and western Hawkes Bay was still largely undeveloped, in most part covered in dense impenetrable forest. For these areas, Vogel was keen to recruit settlers from Scandinavia, who were reputed for their skill as foresters and axemen. It also appears that he may have also been influenced by an early, and rather illustrious settler in the Manawatu – Ditlev Gothard Monrad, former premier of Denmark. Monrad had immigrated to New Zealand, along with his family, in 1866, in a kind of self-imposed exile. Clearly not afraid of hard work, he found a small clearing on the banks of the Manawatu River, in Karere (near Longburn) and, using timber from the surrounding thick forest, built a home and then went on to develop a farm. Continue reading