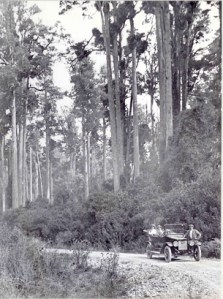

Episode 3 of the envirohistory NZ podcast series is now out. This episode explores three environmental histories – one local, one national and one international. The first story is of Wharemauku Stream, a small stream which runs through Kapiti, but which tells a story that extends beyond its geographical bounds. The second is former Green Party co-leader Jeanette Fitzsimons’ review of the last 35 years and what shifts she has observed in New Zealanders’ attitudes towards the environment. The third story is of Canadian forester – Leon MacIntosh Ellis, who immigrated to New Zealand to take up the first Director of Forests position in the new colony, and shape forestry in this country for years to come.

Episode 3 of the envirohistory NZ podcast series is now out. This episode explores three environmental histories – one local, one national and one international. The first story is of Wharemauku Stream, a small stream which runs through Kapiti, but which tells a story that extends beyond its geographical bounds. The second is former Green Party co-leader Jeanette Fitzsimons’ review of the last 35 years and what shifts she has observed in New Zealanders’ attitudes towards the environment. The third story is of Canadian forester – Leon MacIntosh Ellis, who immigrated to New Zealand to take up the first Director of Forests position in the new colony, and shape forestry in this country for years to come.

16 April 10 Episode 3 – Three environmental histories – local, national and international (12: 35 mins)

Music credit: Polly’s song by Donnie Drost, available from CCmixter.