Further musings on Lord Palmerston, the Great Irish Famine and the future of society

In my last post I talked about the man behind the name of not one but two urban centres in New Zealand, Henry John Temple, better known by ‘noble’ title, Lord Palmerston. I wrote about his inhumane treatment of impoverished and starving Irish tenant farmers on his bounteous estates in Sligo, north-eastern Ireland. His main focus was ridding himself of this wearisome burden, so he (literally) shipped them off to North America. Many died agonising deaths from malnutrition and illness on the way, or once they got to their destination.

In this post I am keen to explore another aspect of this history – a political ideology that has had tremendous influence on our political economy and our lives today. That is, Liberalism. (Noting that its derivative ‘Libertarianism’ is related but distinct in some critical ways but will not delve into this here.)

Because, as well as being a wealthy landlord with questionable morals, and the namesake of several places in ‘the colonies’, our man Lord Palmerston was also the first Liberal Prime Minister. The Liberal Party was first formed in 1859 when the Whig party – the main rival to the more conservative Tories – merged with a couple of other parties with equally radical ideas.

So what is Liberalism? The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Politics tells us that generally speaking it is ‘the belief that it is the aim of politics to preserve individual rights and to maximise freedom of choice.’ More particularly, the Liberals espoused rights of the individual, liberty, political equality, right to private property, and equality before the law. In New Zealand, the first Liberal government premier, Irish-born John Ballance, supported women’s suffrage (in principal anyway) though many of his Liberal colleagues were opposed. (Most notably, Richard Seddon – subsequent prime minister – strongly opposed women’s suffrage because it would be detrimental to the liquor trade, which he had strong alliances with.)

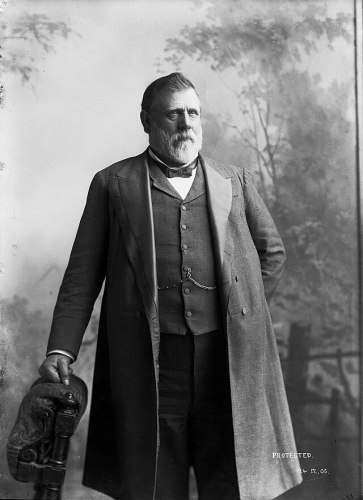

Liberal politician Richard Seddon was not a fan of giving women the vote. Their temperance movement meddling threatened to interfere with the free market and menfolk’s freedom to drink themselves to oblivion.

There is a lot in the Liberal ‘family of ideas’ that modern-day citizens can relate to and support. Most of us probably think that democratic government and equality before the law is good.*

But where it gets complicated is the ideological tenet of maximising freedom of choice – again at first blush this sounds all very jolly hockey sticks, but it has a more sinister side. In economic terms, this tenet translated into the principal of laissez-faire – that is, not interfering in the free market. It also translated into unfettered protection of private property rights – or in the parlance of our current coalition government ‘the enjoyment of property rights’. This is the basis of neoliberalism, the ideology that shapes our political economy today.

Back in the 19th century United Kingdom, by mid-century, both the more conservative Tories and the more radical Whigs had been captured by the thrall of free markets and laissez-faire – but it was the Whig government that took it to its extreme – even where thousands of lives were at stake.

When the Great Famine broke in 1845, the Tory government was in power, headed by Robert Peel (most famous for the establishment of modern policing in the UK – and why the police are affectionately called ‘bobbies’ in the UK). While ultimately inadequate for the scale of catastrophe, Peel did make some efforts to provide relief to the starving poor in Ireland. For instance, he arranged for the importation of corn (maize) from the US and tried to repeal the ‘corn laws’, which imposed tariffs on imported grains, keeping prices artificially high. But facing unsurmountable opposition he resigned, and in 1846, a Whig Government took power, headed by John Russell. This government believed that individuals should be allowed to pursue their own interests to the greatest extent possible with minimal government interference – by providing relief through cheaply sold imported corn, the government was interfering with the market, so this had to be stopped. Equally, the government could not countenance stepping in to stop the flow of food exports from Ireland: throughout the period of the famine, the export of large quantities of grain and livestock out of Ireland continued, mainly to England. Government relief was stopped and it was left to landlords and charitable organisations to deliver relief. In the end, about a million Irish starved to death or died of sickness associated with malnourishment. A further one and two million Irish emigrated.

Ultimately, many politicians and government officials alike believed that the Irish people had brought this misfortune upon themselves. Charles Trevelyan, the official in charge of the famine response, declared: ‘[The Famine] is a punishment from God for an idle, ungrateful, and rebellious country; an indolent and un-self-reliant people. The Irish are suffering from an affliction of God’s providence.’

By now this may all be sounding vaguely familiar. A dominant ideology in our own society is that hard-working New Zealanders should not be giving up their precious dollars for poor people who are doing too little to help themselves. If people don’t live in adequate housing or haven’t got enough money to feed or clothe their kids, it is because they are lazy, or make bad choices or [pick another reason]. This ignores the structural reasons for inequality in our society – some more recent, and some more historical (hint: colonisation, land dispossession). In Ireland, the root cause of the famine was not the potato blight but the gross inequality in ownership and access to land, the consequence of hundreds of years of conquest, land confiscation and dispossession.

In my book ‘An Uncommon Land’, I argue that many of the challenges we face today come back to land, our attitudes towards it (as the ultimate form of private property) and our efforts to accumulate as much as possible of it, to the exclusion of others. Indeed, as Bernard Hickey argues with deliberate but not totally inaccurate hyperbole, the New Zealand economy is ‘a property market with bits tacked on’.

In this laissez-faire inspired political economy, we have been encouraged – indeed rewarded – in our efforts to amass as much wealth as possible. Self-interest is Good. Caring about the wellbeing of wider society, future generations or the planet we depend on is Woke. We see this mentality with brutal clarity in the election result in the United States. We are also seeing worrying signs of it here in New Zealand’s politics. But I am optimistic that we are better than that. I hope that as a society we are willing to question our beliefs about what is really important in our economy and society. Because the future literally depends on it.

* But even something as wholesome-sounding as ‘equality before the law’ has a sinister side. It is this principle of Libertarianism that provides the rationale for the current coalition government’s efforts to subvert and undermine te Tiriti as a founding constitutional document of this country.